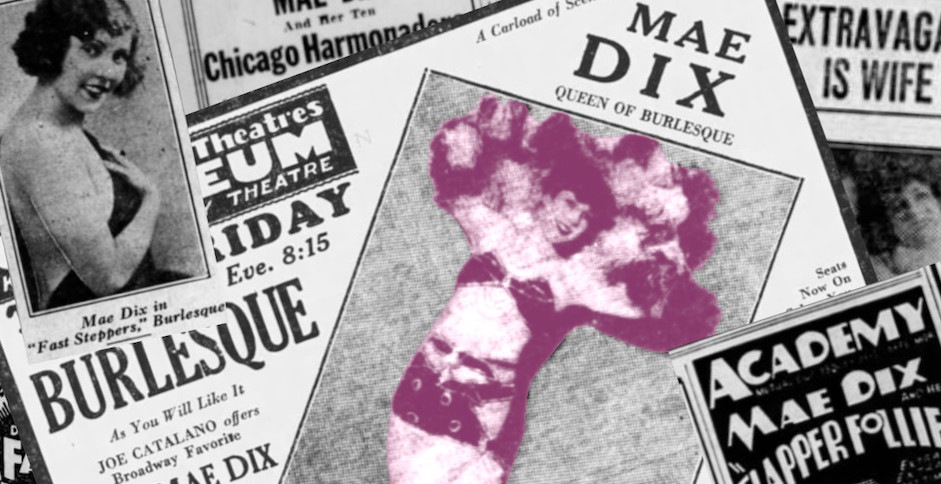

Mae Dix and the invention of striptease

Who was Mae Dix, the burlesque performer who may have accidentally ‘invented’ the striptease in the 10s? She’s often remembered but little known. So let’s discover this artist through the newspapers of her time.

Mae Dix is almost legendary. She is always remembered for the incident which serves to mark the birth of the striptease, but little is known about her.

The informations about her are very few, fragmentary and difficult to find. So we’ve done an in-depth research through the press from the time, reconstructing some of the highlights of the career of the girl that in the 1928 was advertised as The Queen of Burlesque.

Esther Mae Dix was born on September 6, 1895 in the town of Lake Ann, a village in Benzie County of the U.S. state of Michigan. According to unconfirmed reports, in the 10s she worked as a wardrobe mistress for some shows in New York and acted in early movies of the Biograph Motion Picture Company.

When Mae had her lucky accident…

According to the book Minsky’s Burlesque written by Morton Minsky, Mae Dix worked as a soubrette in the shows of Ben Kahn at the Union Square Theatre on Irving Place just before her ‘accidental invention of striptease'(1)Morton Minsky and Milt Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque (New York: Arbor House, 1986), 33-34.

As soon as there was time to do so we hired some really good-looking girls for our chorus and stole a first-class soubrette named Mae Dix from Ben Kahn, who ran the Union Square Theatre.

Mae was a red-haired beauty with a gorgeous figure and a great way of putting over a comedy song. She used to do al the old Anna Held numbers, and believe me that was all we asked her to do. She was a great performer who was starred at Minsky’s before the late 1916 through 1917 season was over.

…

It was toward the end of that season that Mae had her lucky accident. On a stifling hot night she was working in a black short-skirt dress with a detachable white collar and cuffs. They were detachable so that they could be laundered daily, but Mae liked to save a little money and make them do for two days. As she went off at the end of the number, she pulled off the collar, trying to save it as much as she could.The audience saw her do it, and some gagster started applauding for an encore. Mae came back without the collar, raising a storm of applause, bowed, and pulled off the cuffs as she left the stage for what she thought was the last time.

But they wouldn’t let her go. They clapped like crazy, this being a time when a woman on the stage was allowed to show no flesh at all. Between the heat and the applause, Mae lost her head, went back for a short chorus and unbuttoned her bodice as she left the stage again.

…

Once Mae’s accident had happened and the effect of what was one of the first stripteases had been discovered, nothing could have held the audience back. Anyway, we didn’t try. What, were we crazy?Billy gave Mae a ten dollar raise, provided that she repeated the same ‘accident’ every night.

What happened to Mae Dix inspired the movie The Night They Raided Minsky’s (by William Friedkin, 1968).

In 1918 Mae Dix was in the cast of Sliding Billy Watson and the Wonder Show. This information is taken from The Dayton Herald(2)The Dayton Herald, January 1 1918, 11, that dedicated a short article to the private life of Mae:

Extravaganza Star is Wife of Banker

This pretty curly-haired red head, who is the principal soubrette of Sliding Billy Watson and the Wonder Show at the Lyric, will soon retire from the stage, having been married two weeks ago to R. C. Robinson, a prominent banker at Pittsburgh.

We don’t know why Mae Dix changed her plans, but certainly she did not quit his stage career.

Star of Follies

In 1922 she was considered a prominent artist. The Brooklyn Times Union dedicated to her an article entitled “Hard school made Mae a star of Follies”(3)Brooklyn Times Union, March 2 1922, 12, in occasione of her role of chief soubrette of the 14th Barney Gerard’s Follies of the Day, featuring Bozo Snyder.

In 1924 in Dayton, Ohio, she was in the cast of All Aboard. The Dayton Herald published an article about the show, with a statement by Mae Dix about the usefulness of burlesque in society(4)The Dayton Herald, February 28 1924, 10:

Mae Dix Asserts Burlesque Helpful

Mae Dix. the attractive Ingenue in “All Aboard” at the Gayety theater this week, says that burlesque has a purpose aside from entertainment.

“The exposure of human shams and pretenses is one of the chief points of moral helpfulness in burlesque,” continues this little lady. “If a wrong condition will not yield to persuasion, it utterly always can be effectually remedied by making fun of it.

…

That’s why burlesque is a really beneficial in social life. Burlesque ‘bits’ and scenes are always up-to-date and poke delightful fun at flagrant shams and bluffs.

In October of the same year she was in The Fast Steppers, a revue produced by the Columbia Burlesque, advertised as “filling the entertainment desires of the whole family”(5)The Buffalo Enquirer, October 25 1924, 3.

An eclectic showgirl

With the Minskys, Mae Dix has proved she was also a good singer. So much that in 1925 she focused on music in the show Mae Dix and Her 10 Chicago Harmonaders(6)The Lincoln Star, February 20 1925, 8.

The following year she took part in a show at the State and Lake Theater in Chicago. Variety reported that Mae ripped papier-mâché cherries from a bunch between her legs and threw them into the audience(7)Variety, February 10 1926, 36.

In April 1928 she was in the cast of Jazz Time Revue. Even though she wasn’t the star of the show, Variety(8)Variety, 4.4.1928, p. 38 emphasized her impersonating skills:

Not the least of the merits of the show is the performance of a new runway leader in the person of Mae Dix, an energetic Amazon, who does what amounts to an impersonation of Tex Guinan, southern drawl and all, including the catchline “Give this li’l girl a hand.” Good strong arm runway worker, however, and knows her burlesque from St. Louis east, but especially St. Louis.

[…]

Miss Dix was discreet for three numbers and then did one of those shawl manipulating bits for the finale, that was all that could be asked. She is an expert audience worker and in a “pick-out” number had the crowd steamed up to one of the most spirited demonstrations seen at the house in months.

Mae Dix was clearly a multi-talented entertainer: dancer, singer, actress and also impersonator.

In the 1928 – 1929 season she ran her own show: Mae Dix and Her Flapper Follies. A short article on The Baltimore Sun is helpful to understand something about the structure of the shows of this era(9)The Baltimore Sun, February 3 1929, 62:

Flapper Follies For Gayety Theater

Mae Dix And Hindu Dancer Heads Cast Presenting Burlesque

Mae Dix and Her Flapper Follies, with Sharli, Hindu dancer, as an added feature, will furnish the burlesque entertainment at the Gayety this week.

It is announced that the scenic features of the production will include the Land of Dykes, with Dutch setting and costume; Lady of the Vase, in which Dresden figures come to life; the Court of Spain, a dance number, and, as a finale, a blues-strutting shimmy number in which principals and chorus take part. Among those who will appear in the cast are Madeline McEvoy, Ruth Hamilton, Jack Montague, Johnny Ragland, Tom Fairclough and Jess Mack.

In 1932 she was in Chamberlain Brown’s Scrap Book, a revue in two acts at the Ambassador Theatre in New York City.

Curtain.

In 1954 she probably was already retired from the stage and started working backstage, because was in charge of wardrobe for the musical The Girl in Pink Tights at the Mark Hellinger Theatre in New York City(10)Billboard, January 23 1954, 41.

Mae Dix died on 21 October 1958 in Hollywood, at 63, according to unconfirmed reports due to a fire that destroyed her hotel.

Note

| ↑1 | Morton Minsky and Milt Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque (New York: Arbor House, 1986), 33-34 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Dayton Herald, January 1 1918, 11 |

| ↑3 | Brooklyn Times Union, March 2 1922, 12 |

| ↑4 | The Dayton Herald, February 28 1924, 10 |

| ↑5 | The Buffalo Enquirer, October 25 1924, 3 |

| ↑6 | The Lincoln Star, February 20 1925, 8 |

| ↑7 | Variety, February 10 1926, 36 |

| ↑8 | Variety, 4.4.1928, p. 38 |

| ↑9 | The Baltimore Sun, February 3 1929, 62 |

| ↑10 | Billboard, January 23 1954, 41 |